Notes from the field – Jean-Sébastien Boutet

Tataskweyak (Split Lake), northern Manitoba, July 13, 2019:

—Did I tell you the story of when I went to look for porcupine with my dad in 1975?

—No.

—Ok. I will tell you the story of when I went to look for porcupine in 1975.

—Ok…

This past summer I had the chance to travel to Canada to participate in different field schools and explore new research possibilities for my dissertation work in the area of Indigenous economic history. Anthropologists and ethnographers might refer to this period as their “pre-fieldwork,” or “fieldwork: season 0,” but however defined it seems to be invariably made of a strange mix of uncomfortable and rich encounters, a few false starts and some dose of self-doubt.

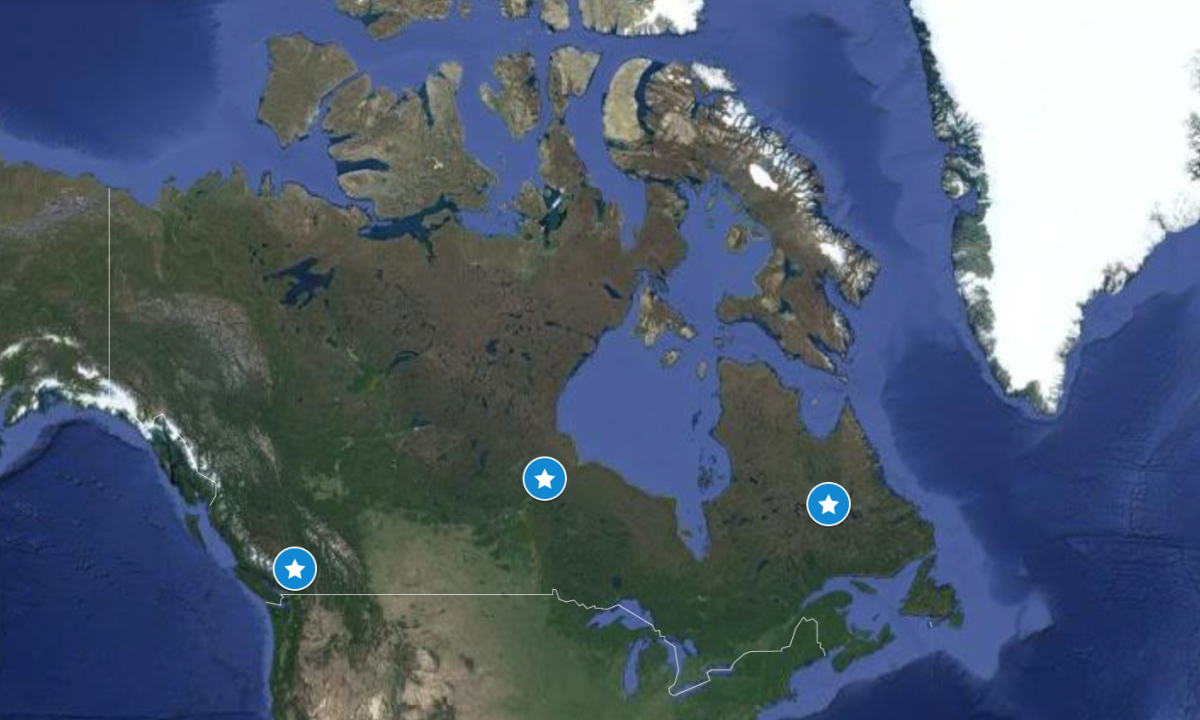

I started the summer in a sense where I began, returning to Schefferville along the Québec-Labrador borderlands where, 10 years earlier, I had conducted fieldwork and written about the region’s mining history. It was special, almost surreal, to come back to this place after so many years to witness all the changes, but perhaps most extraordinarily the continuities that characterize the close-knit and isolated communities who depend, for better or for worse, on the industrial production of iron ore.

In search of words I entered homes introducing myself as a researcher from a decade ago who had come to write about your peoples then and had not returned since. Amazingly, I was offered coffee and a willingness to tell more stories in exchange; some even remembered me, and with a kind of guilty feeling inside I could only produce, like last time, a vague promise to return again, “soon…”

In my masters thesis on Schefferville (2012) I had found it useful to focus my attention on the historical mining period, during which the Iron Ore Company of Canada extracted ore between 1954 and 1982. I was particularly interested in the participation of Indigenous peoples at the mine, explaining that,

if the mining experience in Schefferville evolved in part to the detriment of the Innu and Naskapi communities inhabiting the region, […] these groups also worked to determine their own engagement with the industrial world, adjusting and maintaining their practices notably in order to combine the labour opportunities at the mine with their life on the land.

With these writings in mind, I thought, in Schefferville, about the passage of time. The mining industry, much like researchers, cyclically staging a return as a function of commodity markets, following the devastation of a previous abandonment. Elders whom I once interviewed have now passed, or are travelling to a far away hospital, unsure about when they will be able to return to their family and home community. I’m told there are only about 30 elders left here, people who were born in the forest, sur le territoire. Surely their precious life history must never be forgotten, but how? In the context of today’s reindustrialization process, I wondered if, and how, peoples would adjust their lives to a new mining cycle this time? Will they, unlike the previous cycle, truly benefit from it? For how long?

From Québec I carried on to the west coast for a short stop on the upper canyons of the Fraser River. There was also a going back to the roots of sort, in this case to the beginning of the Canadian mining industry (to my mind at least…). Indeed, on the Fraser, accompanied by incredibly knowledgeable Indigenous guides, rafting superstars and well-respected field scholars, we negotiated a relatively tame portion of the river – the one between Lillooet and Lytton – and visited river bars where, starting in the mid-19th century, Chinese migrants skilfully operated placer gold mines in the most rigorous conditions imaginable. All this, remarkably, almost half a century ahead of the nation defining moment that constitutes, in the Canadian imagination, the Klondike gold rush. Despite the impressive work of scholars who have made these abandoned sites come alive again, there is still much mystery surrounding the composition of social life and labour conditions at the mines, whether these early miners could turn a decent profit, and most interestingly for me, the nature and extent of Indigenous peoples’ involvement with these Chinese labourers.

The third major component of the travels took me to Winnipeg, and from there over one-thousand kilometers by road through boreal forest, all the way past Thompson to northern Manitoba. This one-week long portion of the trip assembled an eclectic group of professors, students and artists dedicated to learning first hand about the impacts of hydroelectric development on First Nations communities in the province. Despite the strong enthusiasm of the group and perpetual humour from our Indigenous guides, this place had a more sombre tone. Compared to former and operating mine sites – such as the Québec-Labrador and British Columbia ones visited earlier –, which are certainly destructive but equally so full of life, or at least full of traces of past lives, there is a deadening aspect to river damming that I find overwhelming, almost hard to take in. In Manitoba we witnessed death: the silencing of the Grand Rapids, today only a sad trickle of their former selves; kilometres and kilometers of eroded river banks, seemingly reaching into infinity on a scale beyond description (one of the main water bodies affected, Lake Winnipeg, is among the largest lakes in the world); the constant buzzing drones of high power lines; houses and school buses abandoned on submerged lands; a drowned moose, sick fish, and the abstract fear of possible methylmercury contamination; to sum it all, some have told us, the near destruction of once-thriving local fishing economies.

With such short time (a total of about one month on the road), I’m inevitably left with only fragments of stories, on the surface apparently distant from one another, which I must somehow make sense of. Like the unfinished porcupine story, from more than 40 years ago, which opened this post; told by our guide along with a contemporary tale about caribou, who had come near the community in great number this year to tell everyone, “if you don’t take care of our land, we will not come back again.” Is there a kind of land morality that perhaps unites these diverse encounters, these generous telling of a story? Certainly this summer I heard many times about our responsibility to care for animals and all that is beyond the short-term promises of industrial development.

It was, at minimum, a productive year zero in the field for me. I was glad to be reminded about the field, how much I love the field, how much I miss it, how difficult and real it is. I remembered where I am most comfortable, at the kitchen table, on the lake, listening to the words and not saying very much, just sometimes awkwardly explaining myself and the purpose of my visits there, in northern Canada. With a note to self, to return, “soon…”

Featured image: Descending the Fraser River in search of abandoned gold mines. (photo by author)